Dislocated Ankle

Read More >

The knee is stabilised by four main ligaments of the knee. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments are responsible for limiting and stabilising forward and backward movements of the tibia relative to the femur, respectively. And the medial and lateral collateral ligaments prevent valgus (inward) and virus (outward) forces of the knee, respectively. Surrounding the knee are muscles that can actively restrain and stabilise movements of the knee, including the quadriceps, hamstring, adductors, and calf muscles. As the knee is a very stable joint, dislocation is a rare injury requiring significant force. Typically, a dislocated knee injury will occur relating to road traffic incidence, high-speed sports injury or an accident such as a foot getting stuck in a hole. A less common but growing cause of knee dislocation is morbid obesity, where dislocations can occur from walking or getting up from a chair, as the knee is already stabilising the knee with the high forces associated with high weight.

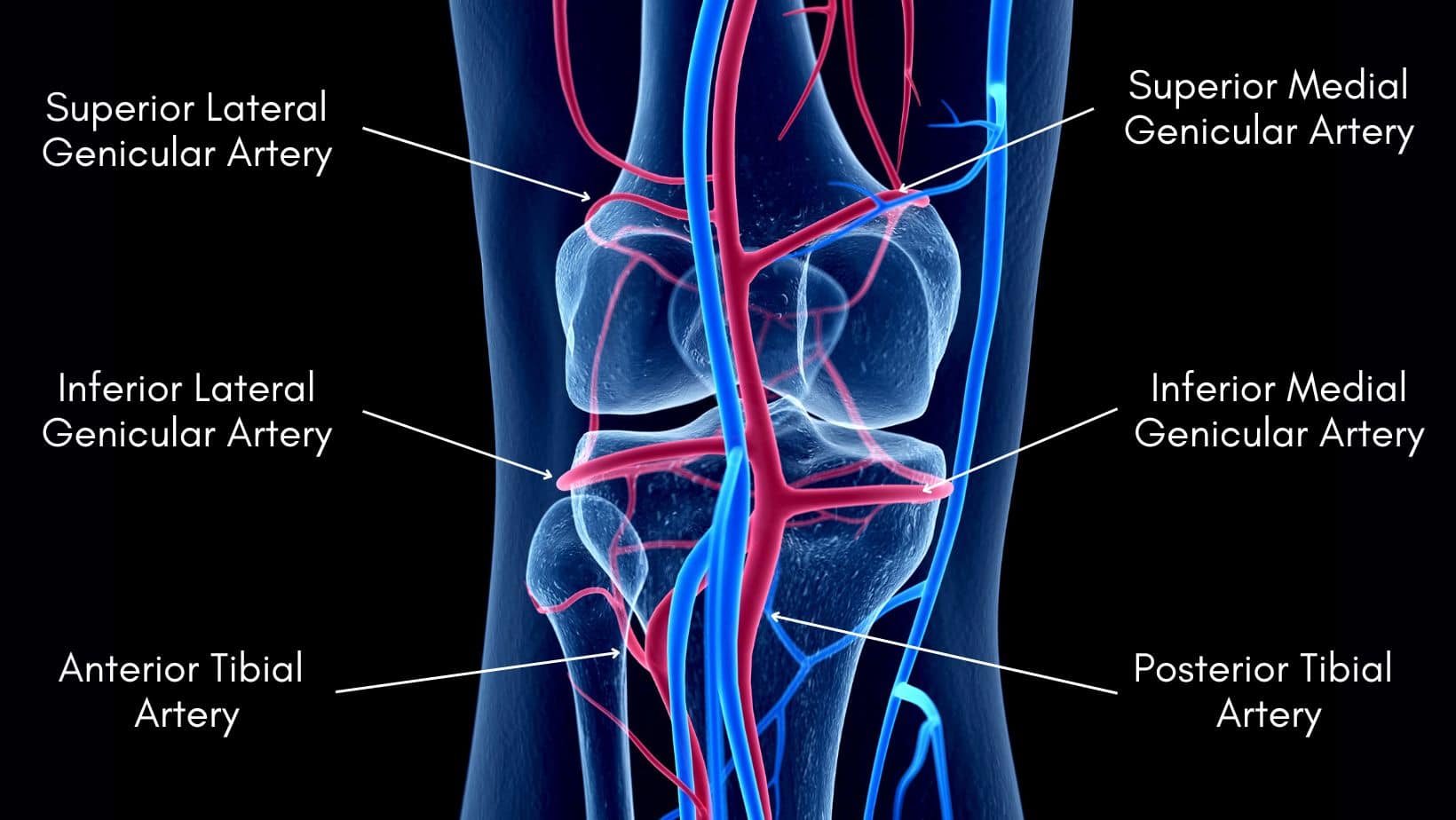

The vascular structures of the knee’s anatomy make a dislocation a serious injury. A dislocated knee can be a limb-threatening injury if these structures are injured. The main blood supply to the knee comes from the popliteal artery, the origin of five separate arteries in the knee, a pair of superior and a pair of inferior arteries, and a middle genicular artery. In addition to this group are the lateral femoral circumflex and anterior tibial arteries. If the genicular artery is injured beyond repair, the other blood vessels are unable to compensate, and the likelihood of amputation will be high.

There are types of knee dislocation, and categorisation relates to the direction of dislocation: anterior, posterior, medial, lateral, and rotary. Further classification of rotary dislocations is also related to the direction of injury: anteromedial, anterolateral, posteromedial, and posterolateral. Dislocations are also categorised as either high or low-velocity injuries.

This will have an impact on the expected outcome and recovery. Low-velocity knee dislocations will likely have lower soft tissue levels and neurovascular injury. High-velocity knee dislocations, such as a floating knee, are likely to have more soft tissue and neurovascular injury and disruption to the joint capsule, meniscus, and cartilage of the joint surfaces.

Forced hyperextension

Road traffic incidents, sports such as football or stepping in a hole.

Force on the tibia with a flexed knee.

Impact on a dashboard, falling onto a bent knee or a direct blow to the tibia.

Valgus or varus forces.

A side tackle from rugby or a sideways fall onto an object.

Rotational forces.

Road traffic incident.

The correct and thorough assessment of a dislocated knee injury to diagnose it accurately is essential, as with any injury. The difficulty with a dislocated knee is that it will often spontaneously reduce (or relocate), by the time the individual has arrived for assessment with a doctor, or at the emergency room. Due to the risk of limb loss due to vascular injury with a dislocated knee, if a dislocation is suspected a full neurovascular assessment should be completed without delay. This will include, but is not limited to, assessment of the skin colour, temperature, and capillary refill of the limb, dorsal pedal and posterior tibial pulses, dermatomes, and myotomes, all of which should be compared to the other limb. Arteriograms are recommended for are more complete assessment.

A neurovascular injury occurs in between 20-40% of all knee dislocations.

Early management is to get the individual to an emergency room for early assessment. The knee may have spontaneously reduced, but if not it will need to be reduced as soon as possible, either closed which is preferable, or open. Once screened for possible neurovascular injury and reduced, the knee will either need to be managed conservatively with splinting or operated on.

Conservative treatment involves splinting the knee in a fully extended position if the patient can tolerate this. It is often chosen for the less active population, if the knee is relatively stable and if the cruciate ligaments are intact. It is necessary to splint the knee for a 3-10 week period, which often results in joint stiffness and dysfunction. Surgical management is more often the better choice for the active population. And reconstruction or ligament repair will be performed, in addition to addressing any other damage, such as meniscus repair or meniscectomy.

Physical therapy depends on the severity of the injury, the specifics of the ligaments injured, and the management choice that has been made. The recovery process is long with all of these treatments and management options, typically taking 9-12 months or longer to recover and start returning to sports activities. Recovery times are longer if fractures of the tibial plateau or femoral condyle occur.

Expectations must be managed as most of these injuries will not make a complete recovery and if the individual was participating in sport to a high level, they will be unlikely to resume to their previous ability.

You can read more about the rehabilitation of the knee for ligament injuries in our related articles: ACL Rehab Exercises, PCL Recovery, MCL Injury Exercises, and LCL Injury Exercises.

Amputation: As mentioned previously there is a high risk of neurovascular injury with a knee dislocation. If this is identified and treated within 8 hours the risk of amputation is much lower, around 11%. If treatment takes longer than 8 hours the risk of amputation becomes around 86% (Henrichs, 2004).

Deep vein thrombosis: The risk of a blood clot is associated with a knee dislocation and the signs and symptoms should be checked for regularly.

Compartment syndrome: Also a risk of a dislocated knee is the development of acute compartment syndrome, which may require fasciotomy.

This is not medical advice. We recommend a consultation with a medical professional such as James McCormack. He offers Online Physiotherapy Appointments.

Related Articles:

ACL Sprain

PCL Tear

MCL Injury

LCL Injury