Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runners Knee)

Read More >

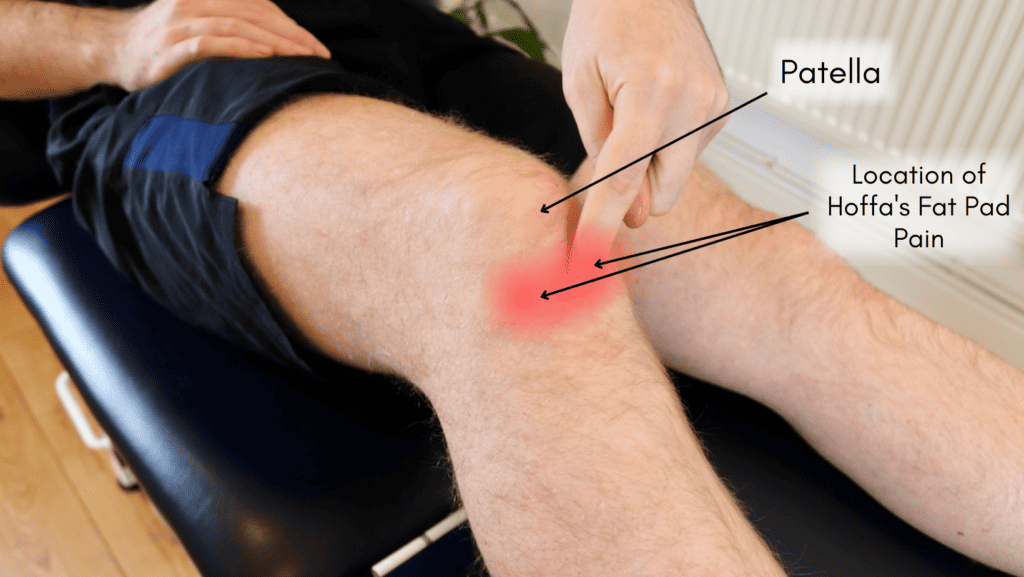

The knee has several fat pads; the one below the kneecap and behind the patella tendon is called the Hoffa fat pad (infrapatellar fat pad).

Hoffa’s Fat Pad was named after the man who first reported on it in 1904, Albert Hoffa. Fat pads are found around the body, and they are large clusters of fat cells that form a protective cushion in areas needing additional help to absorb impact or protect soft tissue from the movement of harder tissues.

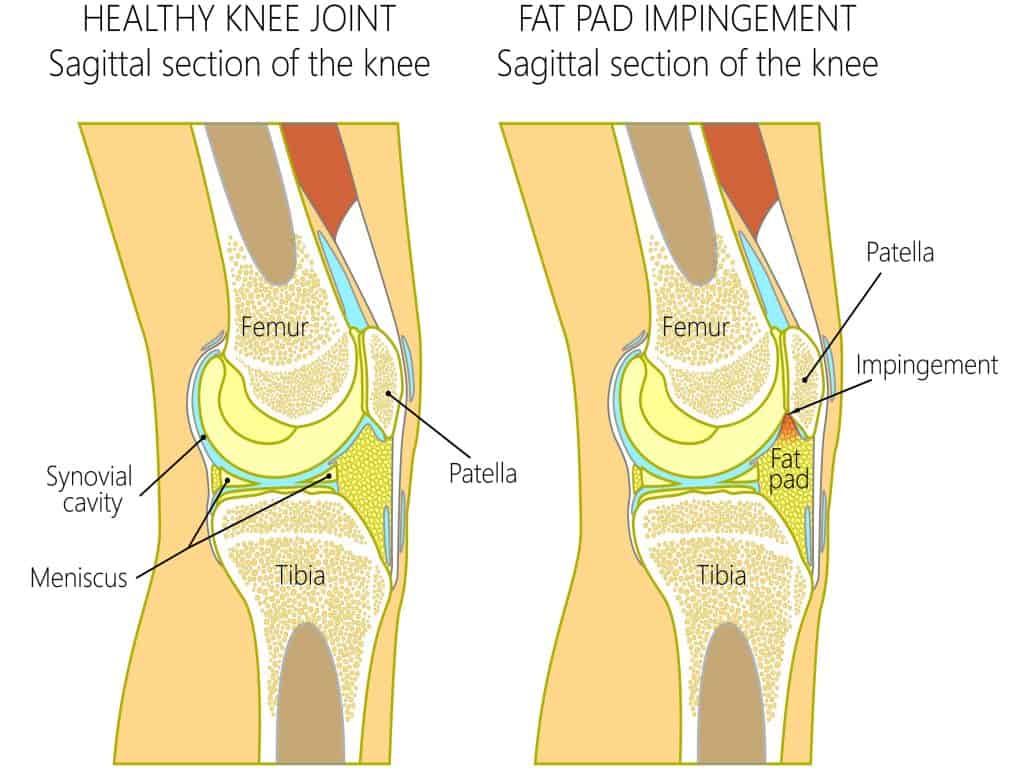

The Hoffa fat pad is located at the front of the knee, and it sits under the patella tendon between the lower border of the patella and the tibial tuberosity. It is a fixed structure inferior pole of the patella, inferiorly by the anterior tibia, inter meniscal ligament, meniscal horns and infrapatellar bursa, anteriorly by the patellar tendon and posteriorly by the femoral condyles and intercondylar notch.

The Hoffa fat pad is a small fat pocket below the knee joint that protects the patella tendon, patella bone, and bone surfaces from the movement of the tibia and femur bones. Despite its appearance similar to adipose tissue, it is highly vascularised, not affected in size by BMI, and receives nerve innervation from the posterior tibial nerve. A superfluity of Type VIa-free nerve endings has been identified within Hoffa’s Fat Pad; they initiate afferent signals of pain, pressure and thermal changes to the central nervous system and are active via fast, sharp pain pathways and slow chronic pain pathways.

There are other fat pads of the knee in positions that need protection. The suprapatellar quadriceps fat pad is above the patella behind the quadriceps tendon. The suprapatellar prefemoral fat pad is also above the patella but adjacent to the femur, behind the synovial membrane. The Posterior fat pad sits at the back of the knee. A further fat pad on the lateral aspect of the knee sits underneath the iliotibial band, just above Gerdy’s tubercle.

Hoffa’s fat pad impingement, also known as Hoffa’s syndrome, occurs when the infrapatellar fat pad (a soft, fatty tissue located below and behind the patella or kneecap) becomes compressed and irritated. This fat pad is situated in the knee joint and plays a role in cushioning and reducing friction between the patella, femur (thighbone), and tibia (shinbone).

There are four main causes of Hoffa’s fat pad impingement: biomechanics, repeated hyperextension in sport, acute hyperextension with an injury, and direct trauma.

Biomechanics: the fat pad is more susceptible to being pinched if the knee is excessively moved into extension (straightening of the knee), such as with hypermobility. Therefore, these individuals are more at risk of this condition. Also, patella mal-tracking has been linked with Hoffa fat pad impingement, especially in younger patients (Subhawong et al., 2010).

Excessive knee extension may include a previous injury to the knee’s ligaments. Damage to ligaments can cause poor control of knee movements, such as knee extension. Repeated compression of the fat pad can cause damage, inflammation, and potentially scar tissue formation. Hoffa fat pad scarring can be seen as a result of injury and subsequent insufficiency of the ACL ligament. (Draghi et al., 2016)

Repeated Hyperextension of the knee is common in some sports that cause full extension of the knee with high force. Fast bowlers in cricket are an excellent example of this.

Other sports can have a greater risk of hyperextension injuries. These tend to be sports where the foot is fixed to the ground, but the body can continue moving. Any sports where studded shoes are worn, such as football or skiing, are examples of this, as well as dancing.

Direct trauma to the fat pad, such as an injury of landing on or getting hit in the knee or a dislocation of the patella, can cause a sudden onset of fat pad pain and inflammation.

The symptoms of Hoffa’s fat pad impingement typically present with pain in the anterior (front) region of the knee. The pain is usually localised on either side of the kneecap, directly beneath it, or, occasionally, behind the patellar tendon.

Alongside the pain, there can be visible swelling and a sensation of warmth, while the skin may appear reddened due to inflammation. Repeated compression of the fat pad, which is highly sensitive due to its rich nerve supply, can cause inflammation and a burning sensation in the fat pad.

The severity of Hoffa’s Fat Pad symptoms is often exacerbated when the knee is fully extended, such as standing with the knee in hyperextension or sitting with your feet elevated but without support under the knees. Standing with a slight bend in the knee can somewhat alleviate the pain.

Activities involving knee flexion and extension, such as ascending and descending stairs, can aggravate the symptoms of Hoffa’s Fat Pad Impingement. Even bending the knee fully may cause significant discomfort in moderate to severe cases.

Most medical professionals will include some general physical assessments, such as looking at how you move, including some of the actions that trigger your pain. Other parts of the assessment will focus on strength, flexibility, and special tests. These “special tests” are orthopaedic tests developed to put more stress on particular structures. In most cases, a combined approach of using “special tests”, a physical examination, and listening to a subjective history will provide the clinician with the best picture to interpret what is causing the issue.

There is a “special test” for the Hoffa fat pad. The test, known as a Hoffa’s test or Hoffa pinch test, involves pressing either side of the patella tendon when the knee is flexed to 30-60º. Repeating the pinch with the knee in full extension should elicit greater discomfort, indicating a positive test. This test has not been evaluated in diagnostic studies.

For additional clarification of the diagnosis, an MRI image of the knee will show inflammatory changes, such as synovitis or inflammation of the fat pad. Other conditions may be present, such as a symptomatic Infrapatellar Plica, lesions or tumours. To confirm the outcome of the physical assessment. MRI may also show other changes, such as scarring or cysts that may have formed (Saddik et al., 2004).

In our experience, activity modification is the most effective way to help settle the irritation and pain of a fat pad impingement. Avoiding hyperextension and reducing activities that aggravate your pain. Targeted stretches and massage to the muscles around the knee, such as the quadriceps, hamstring, and calf, can be helpful, and over-the-counter anti-inflammatories are beneficial.

After an assessment, your physical therapist should understand what has caused you to develop an inflamed fat pad. They should also understand what factors that are specific to them might be continuing to irritate it and, therefore, what modifications you need to make.

For long-term resolution, it is essential to address the cause of the injury. This may improve the proprioception around the knee for someone with hypermobility and increase strength and control of the leg and knee with exercises.

Additionally, looking at walking or running gait can be very important if this contributes to the onset of pain or if it contributes to recovery.

Taping can be effective in helping alleviate the pressure of the kneecap on the fat pad. It can be applied with ridged tape, sometimes called zinc oxide tape, or with elastic sports tapes like KT tape.

Application with elasticated sports tape can be made in many different ways. Trying several different versions can help you find what works best for you. The technique that offers the most pain relief for you is how you should tape.

One version uses three strips of tape in a triangle around your kneecap. Two strips start overlapped from the top of your shin bone and stretch on either side of your knee cap. These are to be attached to the third strip running horizontally across the top of your knee. The bottom two strips should be applied with some stretch to the tape, and the recoil of the tape will help lift the patella to alleviate the pressure on the fat pad.

Hypermobile patients experiencing Hoffa’s Fat Pad syndrome can find their symptoms worse when standing. Trainers or shoes with a high heel drop (the back is higher than the front) can relieve pain by encouraging a slight knee bend. Alternatively, placing a heel wedge inside your should can provide the same benefits.

Recovery time from knee fat pad impingement can vary depending on various factors. In our experience, Knee Fat Pad Impingement recovery occurs within 8 to 12 weeks, but it is important to understand that recovery time is not the same for everyone. For some patients with chronic symptoms, it can take 6 months or more from the time they begin Physical Therapy to recover from Fat pad Impingement.

Here are some factors that can affect the recovery time:

Intervention Techniques: In stubborn cases of Fat Pad impingement that don’t respond to conservative treatment despite your best efforts may require a corticosteroid injection to reduce inflammation and provide a window of opportunity for recovery.

Corticosteroids are strong anti-inflammatories and help reduce inflammation in more severe or persistent cases. Sometimes, settling the pain and inflammation may be harder, and additional treatment is required.

In a minority of cases, a corticosteroid injection will be offered. A consultant, sports doctor or specialist physical therapist usually perform this. Using ultrasound, the cortico-steroid can be guided into the fat pad.

Surgery for fat pad irritation should be a last resort when all other treatments have been exhausted. If activity modification, physiotherapy, taping and medication are ineffective over an appropriate period, such as six months. Knee Fat Pad impingement surgery recovery time can vary depending on the type of surgery, but in our experience, most cases recover within 6-12 weeks.

Partial resection of the infrapatellar fat pad involves arthroscopic resection conducted through specific portals, and inflamed portions of the infrapatellar fat pad are removed with a shaver or an electrothermal probe.

The outcomes of this procedure are generally positive, with one study showing 10 out of 12 patients experiencing good results after an average of 76 months and another study reporting 30 out of 34 patients returning to their pre-injury condition after an average of 68 months.

Arthroscopic debridement addresses an extension block caused by impingement of hypertrophic or fibrotic fat pad tissue following ACL reconstruction. However, statistics reveal mixed outcomes; over 50% of patients reported being completely satisfied with the procedure, but a significant number still experienced mild symptoms even 28 months post-operation.

Arthroscopic resection effectively treats symptomatic infrapatellar plica, which typically appears torn, inflamed, or thickened. Approximately 86-91% of patients undergoing isolated infrapatellar plica release reported few to no symptoms post-operatively.

This is not medical advice, and we recommend a consultation with a medical professional such as James McCormack to achieve a diagnosis. He offers Online Physiotherapy Appointments weekly.